|

|

|

|

Alternate View Column AV-03

Keywords: alternate, universes, quantum, Everett-Wheeler,

many-worlds, interpretation

Published in the November-1984 issue of

Analog Science Fiction & Fact Magazine;

This column was written and submitted 4/6/84 and is copyrighted

©1984, John G. Cramer. All rights reserved.

No part may be reproduced in any form without

the explicit permission of the author.

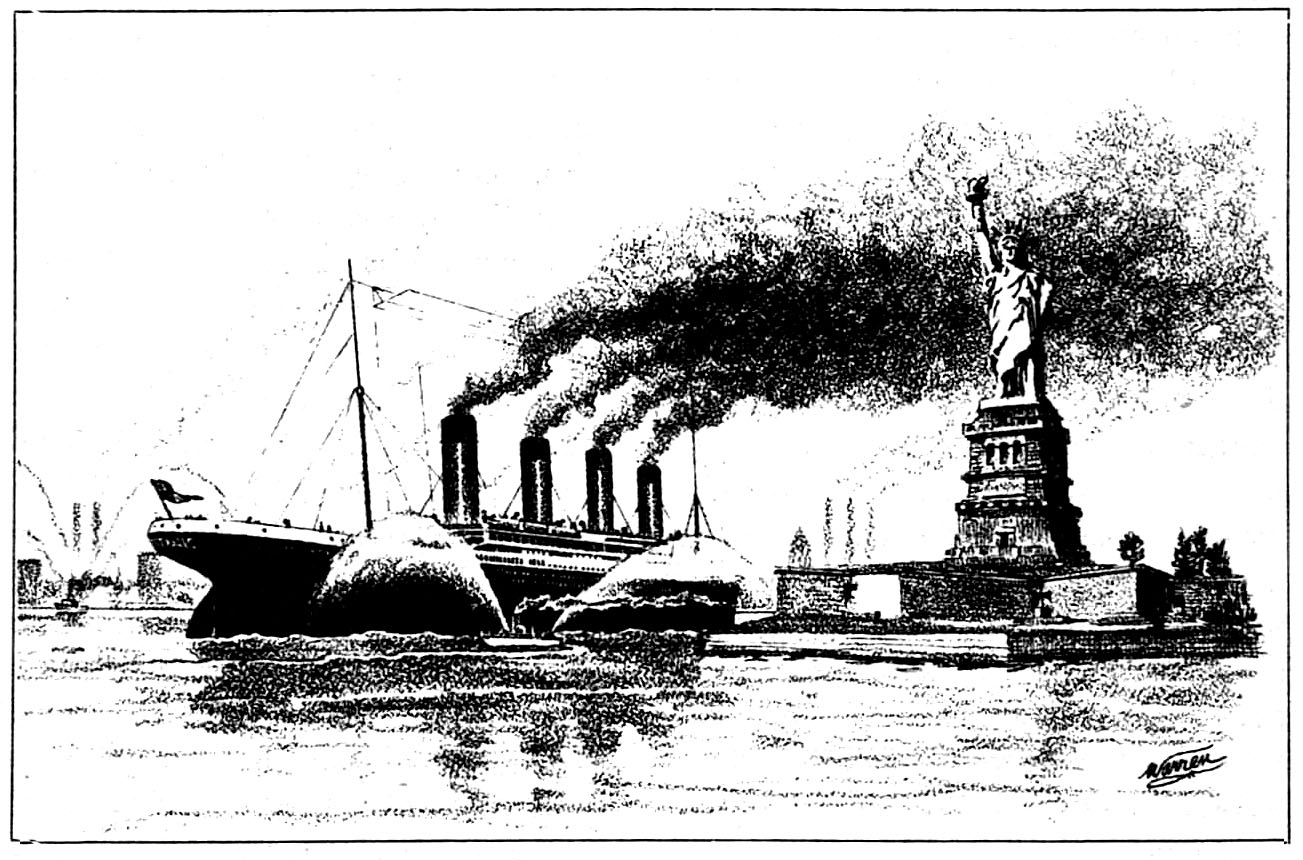

In the fullness of Creation, do other universes exist? Are there alternate worlds where history is not the same? Where in 1912 the RMS Titanic sailed into New York harbor intact? Where the American Revolution was lost to Spanish colonies? Where the Renaissance never occurred, and the Middle Ages have never ended? Where Christ and Mohammed were never born, and the Roman Empire never fell? Where there was no large asteroid impact(s) to kill the dinosaurs and end the Cretaceous, and evolved dinosaur descendants are Earth's dominant life form?

My previous Alternate View column (ANALOG 9/84) described the widely accepted

"inflationary scenario" of modern cosmology in which our Universe is just one

among very many "bubble universes", all popping out of the general medium of

the Big Bang like bubbles forming in a glass of beer. Somewhere perhaps there

are many universes more or less like ours, some very similar to and others

radically different from the universe we call "home".

My previous Alternate View column (ANALOG 9/84) described the widely accepted

"inflationary scenario" of modern cosmology in which our Universe is just one

among very many "bubble universes", all popping out of the general medium of

the Big Bang like bubbles forming in a glass of beer. Somewhere perhaps there

are many universes more or less like ours, some very similar to and others

radically different from the universe we call "home".

This time we examine quite a different basis for the possible existence of alternate universes: The Everett-Wheeler interpretation of quantum mechanics. This rival of the orthodox "Copenhagen" interpretation of the mathematics of quantum mechanics is the work of the well known theoretical physicist Professor John A. Wheeler and his PhD student Hugh Everett, III, both of whom were at Princeton University when the work was done. Their theory also goes under the name of the "many-worlds" interpretation. To understand the basis for this work we shall look at some of the curious and perverse features of the mathematics of quantum mechanics and the problem of its interpretation.

Quantum mechanics (QM) was invented in the early decades of this century to explain a growing body of new experimental facts which didn't fit with the older ideas of "the way things work" which we now call "classical mechanics". The new QM treated particles (like electrons) as if they were waves and treated waves (like light) as if they were particles. A group of physicists led by Bohr, Heisenberg, Schroedinger and Dirac devised clever mathematical ways of "getting the right answer" with quantum mechanics through a set of mathematical procedures which are now used and trusted by all physicists. The use of these procedures is clear and unambiguous. But even now, five decades after their invention, their meaning remains controversial. One often hears that "mathematics is the language of science". Quantum mechanics illustrates the point that this language may lack a proper translation. Formulating a mathematical theory is not the same as understanding its full meaning. The meaning of the QM mathematics has recently become a subject of intense activity and controversy among physicists (including me), as it had been for decades among philosophers of science.

In the orthodox Copenhagen interpretation, the QM mathematics describes not physical events but rather the knowledge of an observer who is watching these events. Equations about mass, energy and momentum are supposedly making predictions about things that happen in the observer's mind! This, as one might expect, leads to problems. The Everett-Wheeler approach is an unorthodox alternative which seeks to avoid these problems. Let's consider an example: A radioactive atom decays, spitting out a rapidly moving electron. In the QM picture of this event a wave corresponding to this electron spreads out from the parent atom in all directions, moving out as an ever-widening sphere, like a ring of ripples from a stone thrown into a pond. The electron is equally present in all parts of the wave. It is "buttered out" over the whole wave front. Finally this wave reaches a second atom which is hit by the electron. Immediately the electron wave undergoes a process called "collapse". This collapse resembles the pricking of a soap bubble, for the wave completely disappears from all of space except the immediate vicinity of the struck atom. There the electron suddenly pops into existence, reappearing as a particle which has just hit the atom. The electron in the form of an expanding wave has vanished.

What if this kind of behavior was also seen in the macroscopic world of everyday experience? Imagine that you stand at a dock on the Manhattan waterfront and toss a beer bottle into the Hudson River. The ripples from the beer bottle spread out across the Atlantic to Southampton, Le Harve, and Lisbon, pass the Straights of Gibraltar and spread across the Mediterranean. Suddenly at the waterfront at Nice a beer bottle jumps out of the water to land on the pebble beach in front of the Carlton Hotel. And simultaneously all the ripples which have been spreading elsewhere around the world abruptly disappear!! If such an event happened, the beer bottle in the everyday world would be behaving the way all electrons do in the microscopic world. This is what the QM mathematics seems to be telling us. It seems a very strange way to get from one place to another!! And it is only one of many examples of the weirdness of quantum behavior.

Most physicists regard this kind of microscopic behavior as normal and refuse to worry about it. They associate collapse with the "knowledge change" occurring when an observer learns an electron's location. Since quantum mechanics works, they use it without being unduly concerned about the bizarre microscopic behavior suggested by the equations. But a few have tried to look more deeply into what quantum mechanics is trying to tell us about the reality behind those useful equations. One such was Albert Einstein, who never accepted quantum mechanics because he found its interpretation unsatisfactory. Another is Hugh Everett III, who found it "unreal that there should be a 'magic' process in which something quite drastic occurred (the collapse of the wave), while at other times systems were assumed to obey perfectly natural continuous laws." Everett did his PhD dissertation at Princeton on the problem of finding an alternative interpretation of quantum mechanics which did not involve collapsing waves or observer knowledge. The result was the Everett-Wheeler interpretation of quantum mechanics mentioned above. It embodies a simple but radical idea.

According to Everett's description of the electron event, the wave never collapses. Instead, at every occasion where the electron might strike one atom or another, the universe splits! We have one universe where the electron hits atom A, another where it hits atom B, and so on for all of its possible outcomes. Similarly, if a light photon might be transmitted or reflected, if a radioactive atom might decay or not, the universe fragments and we get one new universe for each and every possible outcome. The universe, then, is like a tree, branching and re-branching into a myriad of new sub-universes with each passing picosecond. And each of these new Everett-Wheeler (E-W) universes has a slightly different sub-atomic "history". Since our present consciousness happens to have followed one particular path through the diverse branches of this Universe-Tree, we never perceive the splitting but instead interpret the resolution of the myriad of possibilities into a particular outcome as an abrupt "collapse".

Microscopic events, of course, lead to consequences on a larger scale. Somewhere there should be E-W universes in which every physically possible event that could occur has occurred! There should be universes where Man never evolved, where Carthage defeated Rome, where Hitler won, where your present location is a smoking radioactive ruin of World War III. Even as you read this sentence the universe should be fragmenting into a number of branches too large to count.

The Everett-Wheeler interpretation has not been received with overwhelming

enthusiasm by most physicists. It is regarded as multiplying hypotheses beyond

necessity, as William of Occam put it. It is not widely accepted, but it is

much discussed. Many physicists consider it unlikely that nature would behave

in such a schizophrenic way. Many find it harder to swallow the multi-universe

idea than to accept the collapse of the waves. But perhaps the most serious

criticism of the Everett-Wheeler interpretation is that its predictions for the

outcome of experiments do not differ from those of the orthodox Copenhagen

interpretation. Therefore it is an untestable theory. Scientific theories are

normally worth considering only when experimental tests might prove them wrong.

Otherwise a theory is metaphysics, philosophy or myth, but it is not subject to

the scientific method and therefore not science.

But let's lay aside these worries, assume that there really are alternate Everett-Wheeler worlds somewhere, and ask some questions:

Q: Could E-W universes be the same as "bubble universes"? No. The bubble universes should have separated themselves from the medium of the Big Bang in the first picosecond, and thereafter should remain completely unconnected (unless they happen to bump together). They can't be the same as E-W universes.

Q: How might one manage to go from one E-W universe to another? I can only speculate. QM allows physical systems to "leak" from one state to another (example: the alpha-particle decay of uranium-238), so perhaps one could "leak" into an alternate universe, particularly one which was locally very similar to ours. Or given a time machine (a big "given") one might travel back in time to a split-point, then travel forward along another E-W branch to an alternate version of the present.

Q: E-W universes split only going from past to future; doesn't this time asymmetry contradict an important principle of microphysics? Yes it does. But the Everett-Wheeler interpretation can be generalized to a more time-symmetric form by including a "healing" of splits whenever two E-W universes accidentally become completely identical. This is a fascinating idea in its own right. It leads me to assert the Historical Uncertainty Principle: All versions of history which are physically possible and consistent with the present state of our world are equally true and have equally led to the present along various E-W branch universes which healed together to make the present. There is no "right" account of the recent or distant past; all consistent versions are equally correct. (Just think of the implications of that for historians and lawyers!!)

Q: But do you really believe any of this? The

"bubble universes" I find quite acceptable. But for me the Everett-Wheeler

interpretation lacks the "feel" of validity and itself raises too many

problems. To be fair though, I am not really an unbiased critic because I have

my own published unorthodox interpretation of QM mathematics. But that I will

save for another AV column in some future universe.

John G. Cramer's 2016 nonfiction book (Amazon gives it 5 stars) describing his transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics, The Quantum Handshake - Entanglement, Nonlocality, and Transactions, (Springer, January-2016) is available online as a hardcover or eBook at: http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319246406 or https://www.amazon.com/dp/3319246402.

SF Novels by John Cramer: Printed editions of John's hard SF novels Twistor and Einstein's Bridge are available from Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Twistor-John-Cramer/dp/048680450X and https://www.amazon.com/EINSTEINS-BRIDGE-H-John-Cramer/dp/0380975106. His new novel, Fermi's Question may be coming soon.

Alternate View Columns Online: Electronic reprints of 212 or more "The Alternate View" columns by John G. Cramer published in Analog between 1984 and the present are currently available online at: http://www.npl.washington.edu/av .

References:

H. Everett, III, Reviews of Modern Physics 29, 454 (1957).

J. A. Wheeler, Reviews of Modern Physics 29, 463 (1957).

B. S. DeWitt, Physics Today 23 #9, 30 (September, 1970),

and the comments in Physics Today 24 #4 and #11 (1971).B. S. DeWitt and N. Graham, eds., The Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton University Press, Princeton (1973).

M. Jammer, The Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics, pp.507-21, Wiley-Interscience, New York (1974).

|

|

|

|

This page was created by John G. Cramer on 7/12/96.